Re-posted from cei.org.

Review of “Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics Is Destroying American Democracy” (Crown Forum, 2018) by Jonah Goldberg and “Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress” (Viking, 2018) by Steven Pinker.

Goldberg’s “Suicide of the West” is a literate, snappily written, and often humorous defense of Enlightenment values and a broadside against populism. Steven Pinker’s “Enlightenment Now” has a similar theme, backed by an astounding collection of empirical data.

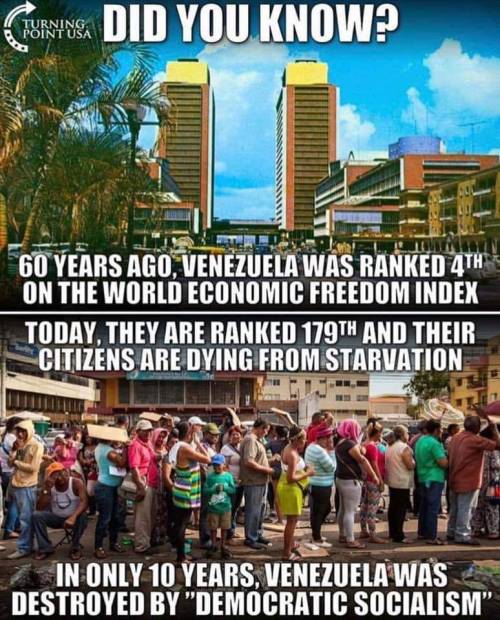

The cooperative social norms that make mass prosperity possible are completely unnatural, Goldberg argues. They are also the best thing that ever happened to humanity, as both argue. The current populist trend is a primal yawp from our baser instincts. It is also the biggest danger the Miracle faces, as Goldberg terms the post-1800 wealth explosion. The average person has gone from three dollars a day to more than 100 dollars a day, at least in countries that more or less adopted Enlightenment values and institutions.

If you doubt the degree of human betterment that has happened over the last two centuries, and how tightly intertwined they are with liberal values and institutions (liberal in the correct, classical sense), even a cursory skim of the first 345 pages of Pinker will show you in great detail. It really is a Miracle, and the most important development in human history since the invention of fire.

Readers who focus on the authors’ criticisms of President Trump are missing the bigger picture. The populist mindset, or rather emotion-set, and not this or that politician, is the biggest threat facing the modern Miracle. President Trump and his analogues in Italy, Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil, and elsewhere are temporary. But the gut-level impulses that make them electable are part of human nature. That is the concern here, not a president who will evanesce from the political scene after a term or two.

Populism is not a left or right phenomenon. It is an anti-Enlightenment worldview based on the immediate, the concrete, and the emotional. A lot of people feel that living standards are declining, and that people aren’t getting a fair shake. The data say otherwise, but a lot of people just feel that way, and form their beliefs accordingly. As Goldberg puts it:

Populist movements do tend to be coalitions of losers. I do not mean that in a perjorative sense but an analytical one. Populist movements almost by definition don’t spring up among people who think everything is going great and they’re getting a fair shake. (p.367)

For many people, their reptile brains override the more analytical parts. If you want to see populist emoting in action, a typical political argument on Twitter, Facebook, or cable news will do. Confirmation bias is rampant, contrary evidence is dismissed, language gets strident, and sometimes things get personal. The flames are as hot as they are shallow, whether they blow from the left or the right. But people still get sucked right in. We’re wired to behave that way.

Populism is having a moment right now, just as it did during the Progressive Era in the early twentieth century, and in the German romanticist movement in the century before that (though that movement was redeemed by some beautiful art and literature). Populism will have more moments in the future. The question is if its latest yawp is merely a blip, or a longer-run rejection of the ideas that make progress and modernity possible.

Like populism, Enlightenment thought works outside of a left-right framework. But unlike populism, it operates on a longer, more cool-headed time horizon. This type of liberalism—again, in the correct sense of the word—is more concerned with abstract cultural values and long-term institutional structures. Having the right long-term process matters more than immediately getting the right immediate results.

Pinker and Goldberg both argue that this patient, abstract approach also explains classical liberalism’s limited appeal. Even when our heads often know better, our hearts are still in hunter-gatherer mode.

It is hard to write news stories about the long-term trends the Enlightenment approach emphasizes. A struggling hometown business with a dozen employees is more emotionally compelling than the fact that worldwide, 137,000 people climbed out of absolute poverty today. One of these stories is rather more important than the other. But it doesn’t fire up people’s reptile brains, so it flies under the radar. Pinker illustrates this phenomenon with graph after graph on a relentless array of policy issues, and Goldberg shows how this affects the quality of both political debate and the politicians in that debate.

Goldberg and Pinker are not alone. Matt Ridley’s The Rational Optimist and Michael Shermer’s The Moral Arc are other quality entries in the genre. Both authors, especially Goldberg, acknowledge the influence of CEI Julian Simon Award winner Deirdre N. McCloskey and her Bourgeois trilogy.

Readers interested in primary sources will find some of the best Enlightenment thought in Adam Smith, David Hume, Thomas Jefferson, F.A. Hayek, and James Buchanan. Populists, knowingly or not, draw from sources ranging from Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Goethe, and Nietzsche up to twentieth century progressives such as Louis Brandeis and Ralph Nader, as well as right-wing populists such as Pat Buchanan and Steve Bannon. Pinker argues that President Trump’s world view is, probably unknowingly, eerily similarly to Nietzsche and Rousseau. Understanding them imparts a better understanding of what makes the current administration tick.

If you don’t have the time to read both books, Reason’s Nick Gillespie had an enlightening conversation with Goldberg in June, and Pinker gave a lecture at the Cato Institute in March. There is some overlap between the two books, but they are far from redundant. The authors’ different personalities and different emphases make for two different, complementary, and important works.