Transaction costs are one of the most overlooked ideas in economics. They are also one of the most important. The lowering of transaction costs is an engine of modernity itself and key to understanding where future progress might take us. That is Duke University economist Michael Munger’s argument in his new book, The Sharing Economy: Its Pitfalls and Promises (free download from the Institute of Economic Affairs). It follows up his 2018 book, Tomorrow 3.0.

What are transaction costs? As the name implies, they are things that get in the way of making transactions. Think of them as economic friction. Things like waiting in line, searching for a product, comparing prices, driving to and from a store, or resetting another forgotten website password. Transaction costs often cannot be measured in money, but they are still part of the price of everything we buy. A good economist knows, money is not everything.

Countless beneficial transactions never happen because the time and hassle required outweigh the benefits. Successful entrepreneurs can make these lost transactions come to life just by lowering their attendant transaction costs. In a way, they succeed by making the invisible visible. Along the way, they can create new industries, revolutionize existing industries, and topple old ones. Transaction costs are the hidden engine of Joseph Schumpeter’s creative destruction.

Munger’s dissertation advisor was the Nobel laureate Douglass North, one of the pioneers of transaction cost economics, along with other laureates such as Ronald Coase and Oliver Williamson. Munger likes to tell a story about North explaining that, while there are endless questions to ask in economics, many of them have the same answer: transaction costs. Over the years, North’s advice has proved useful to countless graduate students in search of thesis topics. As The Sharing Economy shows, there remains plenty of uncharted territory. Today’s graduate students should take note—as should experienced scholars.

How do transaction costs apply to the new sharing economy? Broken down to fundamentals, Uber doesn’t sell taxi rides or food delivery. It sells access to a platform that drastically lowers transaction costs for some services. The product is the platform. Yes, people use it to buy and sell taxi rides and food delivery, but they could use that type of platform for almost anything.

This is why a lot of sharing economy startups describe themselves as the Uber or the Airbnb for this or that service. They’re selling transaction cost savings, not whatever product or service appears in their marketing materials.

Every transaction requires what Munger calls the three Ts: triangulation, transfer, and trust. Sharing platforms can solve the three Ts quickly and cheaply:

- Triangulation means coordinating everyone involved in the transaction. In a food delivery transaction, those are the customer, the restaurant, and the delivery driver. Until recently, solving this coordination problem was so difficult that most restaurants did not offer delivery at all. And the ones that did had to hire their own drivers to work exclusively for them. Unless business was both brisk and consistent, this was a risky proposition. Today, sharing platforms can solve triangulation problems in seconds. As a result, restaurants that might not be able to afford full-time delivery staff can now share drivers with other businesses and earn additional sales, while customers gain additional choices.

- Transfer means making sure everyone gets paid. Uber, for example, has all parties’ payment info stored in the app. It automatically charges customers the right amount, pays restaurants and drivers, and handles tips. That is far easier than in the old days of cash, checks, or reading out your credit card number over the phone.

- Trust is all parties having confidence that everything will go as it should. This is what ratings systems contribute. Riders can avoid drivers with low ratings and drivers can avoid problem customers. They can do this in seconds just by glancing at their ratings. On the other side of the coin, high ratings can be lucrative for vendors, giving them a greater incentive to keep customers happy than a traditional cab driver. And keeping that five-star rating can encourage more civil behavior from customers. It doesn’t pay to be a Karen.

Sharing economy platforms solve the three Ts so quickly and easily that millions of transactions that would never have happened a decade ago are now routine. This, for Munger, is a reason for optimism. Similar platforms could emerge for all kinds of goods. In fact, they probably are doing so right now in a dorm room or a garage somewhere.

Tools that spend nearly all of their time in storage could be rented out, for example. Other possibilities include office equipment, professional-grade audio and video equipment, and designer clothing. Some of these ideas might be successful. Others might be duds. People will likely find out soon enough.

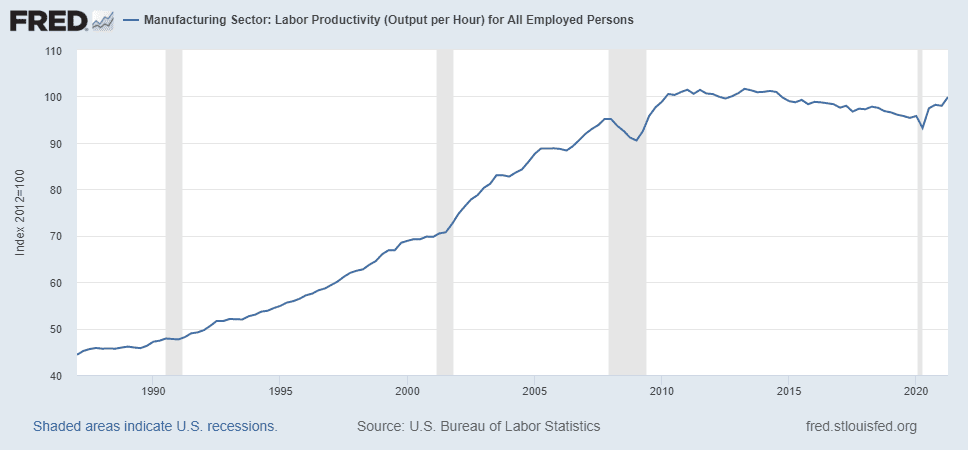

Munger believes the low-transaction cost sharing economy could transform manufacturing as we know it. Factories would make far fewer goods, and what they do make would tend to be professional grade and more durable. A drill that spends 30 years in someone’s garage might get a couple hours of use over its entire lifespan, but if it’s shared, it will get far more use on a wider variety of tasks. It will need to be more solidly built and easily repaired.

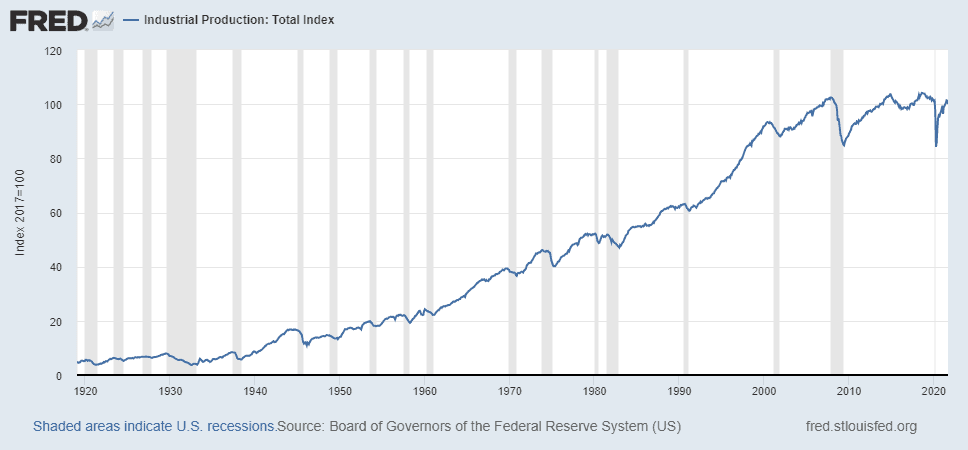

That is one reason why the sharing economy has costs, as well as benefits. Both words in the phrase “creative destruction” are important. Just because the benefits outweigh the costs doesn’t mean costs do not exist. Manufacturing jobs have already declined by about a third since their 1979 peak, from about 18 million workers to about 12 million. If sharing platforms become popular for a lot of goods, that decline will be deeper and steeper. At the same time, the higher-grade goods still being made might require more skills or more automation to make, displacing less skilled workers.

Other jobs would open up in warehousing and delivery, and likely in other sectors. Munger doesn’t know what these might be, and neither does anyone else. Some of these jobs might not be appealing, might not pay as well, or may not work with some workers’ family responsibilities or other personal situations.

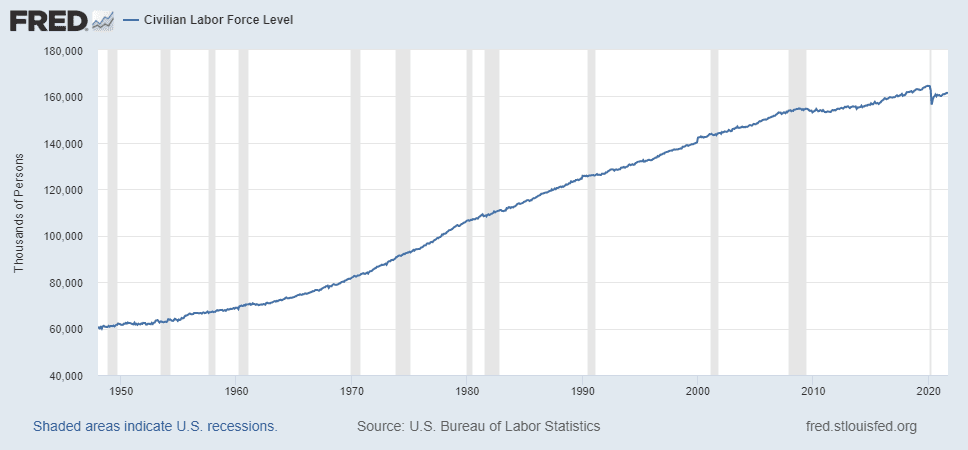

On the other hand, the size of the labor force has stayed remarkably consistent relative to population throughout America’s transition from agriculture to industry, and from industry to services. While the inability to predict the future is scary, that’s no reason to keep things as they are. As Munger says on page 89, “Platforms are disruptive, but outlawing disruption has never worked.”

Transaction Costs and a Policy Revolution

If an accountant uses a platform like Taskrabbit to work for several clients, is she an employee of any of them? Does she count as Taskrabbit’s employee because it handles her payments or is she a customer who pays to access its platform? Does it matter if she commutes to an office or works from home? What if she’d rather choose her own health insurance or retirement plan? My colleague Iain Murray explored this question in his 2016 CEI paper “Punching the Clock on a Smartphone App.”

Current regulations don’t have good answers to these questions. And laws like California’s AB5 gig worker law and the proposed PRO Act at the federal level would entrench the legacy labor law model even further. All this is because some entrepreneurs thought of a way to use smartphone apps to reduce transaction costs.

In the age of COVID, sharing platforms have made it easier for workers to avoid public transportation and crowded offices. When COVID subsides, many workers will still prefer to avoid commutes and offices in favor of more pleasant surroundings like home offices, coffee shops, or smaller shared offices—which some sharing platforms offer. Regulators should think carefully before they take those options away.

Antitrust policy is in the middle of its own revolution, thanks in part to transaction costs. Sharing platforms are just another version of the old make-or-buy decision. If a company needs legal help, does it use in-house counsel or hire an outside attorney? Should a firm employ its own custodian or hire a cleaning service? The answer depends on transaction costs. If it’s cheaper to do something yourself, do that. If transacting with someone else costs less, do that. The answer is different for every company—and can change over time within a company. Sharing platforms and their lower transaction costs provide new possible answers to this age-old problem.

As of this writing, the leading food delivery platforms are DoorDash, UberEats, and GrubHub. They could buy out smaller competitors or merge with each other in the coming years, which might result in antitrust action. It shouldn’t, and transaction costs explain why.

A restaurant that wants to offer delivery has a make-or-buy decision to make. Does it hire its own driver or outsource to a sharing platform? It will go with whichever has lower transaction costs. This provides a built-in competitive check on sharing platforms that will never go away—even if one sharing platform monopolizes the entire market. If its fees cost more than the restaurant hiring its own drivers, then restaurants will opt for the latter. Several restaurants in the same city could even band together and jointly hire a driver—if regulations allow them.

The reason people use sharing platforms in the first place is because their transaction costs are lower than the alternatives. And the alternative of doing something in-house will never go away. Sharing platforms do not have market power, and never will.

Sharing platforms also do not restrain trade, which is another threshold for antitrust enforcement. They enable new trades that would never have happened otherwise, because they lower transaction costs. Before sharing apps, food delivery options in most places were limited to pizza and Chinese. Now, everyone from McDonald’s to mom-and-pop diners offer delivery. Some restaurants, such as Panda Express, are even attempting to undercut sharing platforms by creating their own app-based ordering services to avoid platforms’ fees.

Transaction Costs and the Moral Economy

Contrary to popular belief, morals are an integral part of economics. One of the discipline’s founding works, after all, is Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments. Man is an animal that trades, to paraphrase from Smith’s other great work, The Wealth of Nations. People want to exchange, cooperate, and compete. It is our nature. But transaction costs get in the way of our nature, because they get in the way of trade.

Economists Virgil Storr and Ginni Choi, of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, argue in their book Do Markets Corrupt Our Morals? that markets are moral playgrounds. When people enter those playgrounds, they learn how to trust and earn trust. They learn to keep their word and be polite—the late, great Steve Horwitz delighted in the “double thank you” that accompanies most transactions. People on the playground learn that the best way to get something you value is to give others things they value even more.

These are skills that take practice and repetition to develop. Transaction costs raise the cost of this moral practice. And when something costs more, people consume less of it.

If the goal is an open, civil society, then transaction cost reduction should be an important priority. Sharing economy platforms have the potential to do exactly that on a massive scale. At the same time, they are just another chapter in a long story, and hardly the final one.

Munger, by taking Douglass North’s advice, has used an old and overlooked tool to better understand new technologies and emerging economic changes. Sharing platforms have already changed the way people take cab rides, order food, and go on vacation. In the coming years, they could reshape the manufacturing sector, office culture, and even urban design, if traditional offices and downtowns continue to fall out of favor.

Transaction costs can also lead to fresh insights about labor regulations, antitrust, and other areas of public policy, as well as the overlooked symbiosis of markets and morality. Though The Sharing Economy is geared to a British audience, American readers will still get far more value from this freely downloadable book than they spend in transaction costs. While this admittedly sets a low bar, I intend it as high praise. I could not recommend this book more highly.

Download The Sharing Economy for free from IEA’s website here.